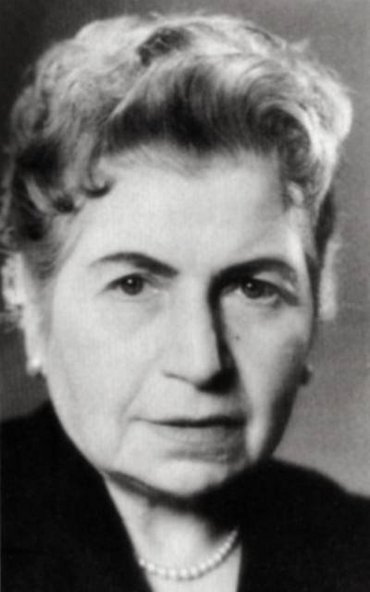

Jeanette Wolff: I Survived Riga...

Jeanette Wolff: I Survived Riga...

Jeanette Cohen was the eldest of six children. At the age of 16, in 1904, she began her training as a kindergarten teacher in Brussels and subsequently worked as a kindergarten teacher and educator. She lived alternately in Brussels and Bocholt, where she met Philip Fuldauer, a Dutchman. In 1908, the two married and moved to Dinxperlo in the Netherlands. On 4th December of the same year, their daughter Margerieta was born, but she died as an infant in September of the following year; two weeks later, her husband Philip also died. The young widow moved back to Bocholt the same year. Also in 1909, she passed the emergency school-leaving examination. In Dortmund, she met the merchant Hermann Wolff, whom she married in Bocholt in 1911. They had three daughters, Juliane (born 1912), Edith (born 1916) and Käthe (born 1920). In 1932, the family moved to Dinslaken.

Shortly after the NSDAP (Nazi Party) took power, Jeanette Wolff was arrested because of her campaigning for the SPD and held in "protective custody" for two years. After her release in 1935, she opened a boarding house for Jews in Dortmund. There the family became victims of the November 1938 pogroms, and her husband Hermann was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp shortly afterwards. The youngest of the children, Käthe, was deported the following year and died in the Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944. Jeanette and her two remaining daughters lived through World War II until 1945and went on an odyssey through various ghettos and camps. Wolff was deported to Riga in 1942 and engaged in forced labour in the Riga-Kaiserwald concentration camp. After the Riga concentration camp was dissolved, she was transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp, where she saw her husband for the last time. When the Red Army liberated her, out of the Wolff and Cohen families, only Jeanette and her daughter Edith had survived the Holocaust.

Report by Jeanette Wolff from 1947:

Deportation

In January 1942 we were deported. We had already been ordered to be deported in October 1941; for some reason the transport was postponed until January 1942. That's when the ominous evacuation letter from the Gestapo fluttered into my apartment: "On 20th January 1942, at 8 o'clock in the morning, you and your family are to report to the large stock exchange hall in Dortmund in order to be sent to work in the East." This letter specified exactly what luggage each person could take with them, 10 RM in money was allowed, everything else had to remain at the disposal of the Gestapo. I must say in advance that most of the Jews had already been expelled from their homes and taken to a damp barrack camp by the canal. There they were crowded together. Linen, furniture, and clothing were, for the most part, confiscated by the Gestapo.

I set out for exile with my husband and my two older daughters; I had to leave my husband's mother, who had lived with us for 28 years, behind. For three days, we were housed in the large stock exchange hall. Guarded by Gestapo officers, we squatted on our luggage. The nights we spent there, together with about 1400 other people, were terrible: we had no opportunity to take off our clothes, we were mocked and mistreated. We were allowed to wash ourselves makeshift in the toilet. We were examined - the women even gynaecologically - to see if we had more than 10 marks. Our wedding rings, which we had not had to hand in after Kristallnacht, were taken from us. A Jewish hatter was shot by Gestapo Commissar Bovensiepen.

Small musical instruments were allowed to be taken along, and the Gestapo demanded that our girls, who had made some art accessible to their co-religionists in the Jewish Cultural Association during the theatre blockade for Jews, play for them, the Gestapo people, and they amused themselves in a special room while the deportees were being guarded. My daughter Edith had taken her lute with her, to which she sang songs in the Kulturbund. She - as well as some other young girls who were called upon - smashed their instruments at a buffet and refused the Gestapo's request.

At four o'clock in the morning of 27th January 1942, we were taken in a roundabout way to the north side of the station, loaded into discarded, totally dirty 4th-class wagons whose toilets were frozen to the top; wagons that were no longer even usable for troop transport. We were crammed together in these unheated wagons; only the so-called ambulance wagon and the wagons for the accompanying field police and Gestapo men were heated. Where we were going, we did not know. Only when we were on the train did it slowly leak out that we were going to Riga in Latvia.

All those scheduled for deportation were asked beforehand to buy mattresses, stoves, sewing machines, blankets, etc., since they were to be used for work in the East. Many wagons with these things were attached to the train, and the suitcases were also taken along. On the orders of the Gestapo, the Jewish Community of Dortmund had raised several provision wagons full of food for the deportees' transport. All these wagons were unhitched in Königsberg, so that we actually had only what we carried with us, packed in rucksacks, and what we had on our bodies. It was an exceptionally cold winter; on the way some elderly and sick people froze to death. The snow was very heavy. Locked in the unheated wagons, without anything warm, without food and without the possibility of washing, we travelled for five days and nights. When we asked the escorts to let us go out, we had to clean the lavatories in each wagon with our hands and without tools. This, apart from the rising disgust, was terrible work in the bitter cold. Finally, after much pleading, some people were allowed to go out of each wagon for water - we were almost parched - and then we were allowed to clean ourselves for five minutes outside in the snow in a makeshift manner. Male and female together; for the women and girls a terrible business. If the SS didn't consider us fast enough, there were also blows from rifle butts. When Mr. Appel from Dortmund refused to go outside to relieve himself in front of the women and wanted to protect his wife from being seen by the men, a field policeman hit him several times on the head with the butt of his rifle until he collapsed. My daughter Juliane later bandaged him up and nursed him and his wife, who was crouched on the bench next to her husband, completely collapsed. We were treated cruelly, but compared to what awaited us in Riga, it was child's play.

We saw a deep blue sky, a golden sun shining on a virgin white blanket of snow; a fairy tale landscape - but the cruel reality quickly made this ray of hope disappear. With whips and clubs, we were herded out of the wagons by SS men. Stiff from days of sitting, crammed tightly together, people were barely able to jump down from the high running boards of the wagon. They were pushed down, kicked, beaten. All that could be heard was the screaming of the SS, the thudding of the blows, the whimpering of those who had been hit. What little of our belongings we carried in backpacks and hand luggage was taken from us with blows or dropped when sharp blows with clubs, whips, or rubber truncheons hit the hands that carried them. Usually, the hand luggage contained some food and toiletries. And yet some of us managed to bring the things that were so precious to us into the ghetto, even if our hands were covered with wounds.

Large sledges that looked like rafts stood a little apart. The purpose of these sledges became clear to us when the SS ordered all those with difficulty walking to sit on them. We wanted to believe in something human in our tormentors, but then we saw how a boy of about ten years of age, who was somewhat lame, was roughly torn from his mother's hand and thrown onto the sledge. The sledges were driven into the nearby woods, and soon we heard the shots that ended the lives of those unfortunates. We were overcome with horror. But worse was yet to come. A man from Dortmund, about 40 years old, was picked out of the arrivals by SS men and shot before our eyes, shouting, "So, you race defiler." I knew the man, he had eaten with us for years, I knew he had lived for more than 15 years with a non-Jewish woman who had been incapacitated by an accident at an early age, and who he took care of touchingly.

The first deportation train left Gelsenkirchen in the early morning of 27th January 1942 in freezing cold. Jeanette Wolff and other Jewish people had to board the train at the stop in Dortmund, and wagons were attached. This train went via Hanover, where more wagons were coupled on, and further via Königsberg, finally reaching Riga in Latvia on 1st February 1942 with more than 1000 souls.

Riga, Moscow Suburb - the Ghetto

The move into the ghetto was only a continuation of the harassment to which we had been subjected at the Shirotawa station and on the way. All documents, work records, identification cards, everything that was considered to authenticate our person was taken away from us, only a few photos of our relatives were left. Our personality was extinguished. Driven by the SS on the one hand and the desire for warmth and shelter on the other, we all pushed and shoved our way to the houses assigned to us upon entering the ghetto. Inside, the houses were like a heap of rubble. On the stairs lay laundry, clothes, and dishes, along with rubble and stones. We were ushered in with blows from sticks, kicks, and shouts. We, that is to say, my husband, my daughters Juliane and Edith, and I, along with 14 other people, were assigned three rooms with the order to clean the apartment and stairs within four hours.

The ghetto was the former so-called Moscow Suburb of Riga. The Latvian Jews had been put there by the Germans; we saw from the clothes, shoes, linen, etc., which had been trodden in the dirt, as well as from the books and crockery, that educated people had lived here who had been forced out only a short time before our arrival, and unsuspectingly at that. There was cooked food on tables that were laid. The expellees had smashed what they could in such a short time. Space had to be made in the ghetto for those deported from Germany, so the Latvian Jews were driven out of their houses to their deaths.

Many people living together in one apartment was not easy. In addition, there was no water, because the water pipes in the apartments were partly frozen, partly destroyed. To get water, one had to walk for about 10 minutes in minus 40 degrees. People stood in long lines with buckets and other vessels to get the precious liquid. How were we to clean the apartments and stairs in the time limit given to us? Many were desperate for fear of the SS, but we still managed, with mutual help, to clean up the biggest mess.

We wanted to light a fire to warm our frozen bodies a little, for this cold was something unfamiliar to us. Since the chimneys were smashed on the inside, acrid smoke penetrated all the rooms. When the SS came to inspect us, our apartment was full of smoke; the SS raved and ranted, and when I said that the smashed chimneys were to blame, I got my first slaps in the face. The morning after arrival came the order: food distribution. There were 215 grams of sticky bread per head, a head of cod, 30 grams of barley and rhubarb leaves or beetroot leaves, scraps from canneries and big hotels. There was no fat at first. We were very hungry. I still remember my husband's first birthday in the Riga ghetto. His birthday present was half of our bread ration, which the girls and I did without.

It was the custom in the ghetto, that, as soon as new transports were reported, people were murdered to make room. Later we learned from eyewitnesses, Latvian Jews who had their own ghetto across the street from us, separated by barbed wire, that about 30,000 people (Jews) had been robbed in the houses in which we were housed. This was done by the Latvian SS under the direction of the German SS - they were robbed, moved out and then murdered in the Bickernick Forest near Riga. In the main they were women and children. The victims had to dig the pits themselves, line up fifty at a time at the edge of these mass graves, and then the machine guns began their cruel work. The living and the dead were buried together. The Latvian SS, scum of the earth, freed in part by the German SS from the penitentiaries of Latvia for the cruel job of solving the Jewish question, were the executioners' slaves. The German SS leaders, the ghetto commander Krause, the Oberscharführer (SS Staff Sergeant) Seekt, the later commander of the Jungfernhof camp, the cynical chief murderer SS-Major Dr Lange and many others of the same calibre sat in warm fur coats and winter boots, smoking cigarettes, on the benches of the park and watched with amusement the goings-on of their drunken executioners.

The highlight of the game was shooting at live children. Two SS men threw the live targets, small children, at each other while a third shot. The German SS also took an active part in this cruel sport. My son-in-law was also one of the survivors, he managed to free himself from the corpses lying above him after the SS had left and got to the Latvian ghetto in the night by a roundabout way. His mother and both sisters were among the murdered. It is impossible to reproduce what happened before the shootings in terms of rapes, screams, nervous breakdowns of people who had gone insane.

The ghetto consisted of various districts named after the transports that arrived. The Hanoverian, the Saxonian, the Bielefeld, the Cologne, the Kassel, the Berlin, and the Dortmund districts. There were about eleven transports of about 2000 people each from these areas sent to the Riga Ghetto. Many did not even get there. Many men were sent to the hell of Salas Pils as soon as they arrived. Of these, not 20 percent remained.

Many transports arrived. There was no more room in the ghetto, as three or more families were already living in one room. The commandant of the ghetto, Karl Wilhelm Krause, formerly a medical assistant in the hospital at Herne (Westphalia), later a manor owner in Upper Silesia, had a splendid method of creating space. In agreement with the head of the Riga SS, Dr Lange, who in turn acted according to Himmler's instructions, either actions were carried out to decimate the ghetto, or whole transports were led straight from the Shirotawa station to the Bickernick Forest. Of one Berlin transport, about 1300 people, including 750 children from the Berlin orphanage, only 80 strong men remained by luck and were sent to Illgeziem to the cement works. Only the clothes and shoes of about 750 children and about 450 women and men were sent to the ghetto. Some of the laundry was soiled with blood.

Berlin action

In January 1942, an SS action was carried out in the Berlin and Vienna districts. Hundreds of elderly people or those who were ill and debilitated by frostbite and privation were herded onto tin cars with rubber truncheons and finished off in the Bickernick Forest. My two daughters, as medical orderlies, had to search for corpses and identification cards in the abandoned houses. They found corpses smashed beyond recognition, others missing their ring fingers, because the fingers had been cut off if the ring was too tight, yes, even the dental bridges, which had gold on them, had been ripped out of the still warm corpses. Later, in spring, when the ice and snow melted, many amputated fingers were found. Bloodstains were exposed which, even after two years, could not be removed. Small actions and executions took place every day, so I will report on the larger ones first.

Dispatch to Dünamünde

Each district had its own administrative office, headed by a so-called elder. In these offices the inhabitants of each district were registered, of course in accordance with the complete index of the Kommandantur (Headquarters). It was from these district offices that, by order of the Kommandantur, people were assigned to the work detachments. The offices were ordered to select people who were weakened or already elderly for light work in the canneries in Dünamünde. All those who were required to be sent were designated by name by the commandant's office. Skilled workers were needed and therefore usually spared from such actions. I had given my profession as uniform tailor, and so I was spared.

If an unjust elder had someone he wanted to do away with, they were put on the list to be sent away. My oldest girl had also been put on the list by the chief physician, Dr Aufrecht, and it was only through consultation with the police lieutenant Heser, who spoke to the commandant, that I was able to keep my daughter, who was 28 years old at the time. The Schutzpolizei (civilian police) then told us that this deportation was a planned extermination. We were indescribably distressed.

When the transports were ready - mostly women and men over 50 and the weak - the eyes of even the most unsuspecting were opened. All of them were death candidates. Blankets, bags, provisions, everything was taken from the unfortunates by the SS. With repeated blows they were loaded one after the other onto trucks, which returned after 30 minutes to fetch new victims, until the last ones had been taken away. I can still hear the wailing and crying of the relatives who stayed behind. The journey to Dünamünde by car took more than half an hour; no one ever returned from there, no Jews ever arrived in Dünamünde. However, so-called Hochwald squads were then formed in the ghetto, consisting exclusively of strong young men. They had to bury the naked corpses and pour chlorine and corrosive chemicals on them. From these squads, only some men came back, by chance. This Dünamünde action claimed about 5,000 victims.

Salas Pils

Again and again, strong young men were sent to the hell of Salas Pils. The treatment there was terrible, for even the slightest transgression was punishable by death. Thin soup made from rhubarb leaves or other waste, 220 g of bread a day, sleeping in dirty barns with only one blanket, no chance to wash, no drinking water, hard work in brickworks or quarries, that was the "life" of these unfortunates. If you became ill, you received only half rations in addition to all the other tortures. Eighty percent of these people perished miserably because there were no sanitary facilities of any kind. Typhus and dysentery were the cause of death for half of them, the others were beaten to death, hanged or, if they were lucky, shot. About 7,000 to 8,000 people perished there between 1941 and 1943. Many relatives and close acquaintances of mine were among them.

Just a few things about life in the ghetto: For the first 14 days there was no food at all. We searched for frozen potato peels, vegetable scraps, etc. from the piles of rubbish, cleaned them, cooked them, and ate them. We also found remnants of flour or grain here and there among the debris. We mixed potato peels with a little flour and baked a potato pancake out of it, without any fat. Sometimes military vehicles drove through the ghetto with bread. When they stopped, we would get bread. The first rations we got were mouldy bread, 220 grams per head per day, later fish and kipper scraps from the smokehouses were added. Rhubarb and beetroot leaves, spinach and cabbage scraps, sauerkraut, but almost all stinking and rotten, that was then our food. If we hadn't gone out on work detail, we all would have starved to death. Nevertheless, a great many people died of exhaustion and, above all, of frostbite.

Many things were banned in the ghetto. I do not want to keep some of them from posterity, as they show only too well the Nazis' level of culture. To place a guard at every sleeping place now was impossible even for Commandant Krause, but nightly checks to prevent mating were to serve as a substitute. Children were not allowed to be born, pregnancy terminations, even in the sixth month, or even beyond, were carried out without anaesthesia but with the participation of interested SS men. The commandant was also present at almost every operation.

A young woman known to me had an abortion in her seventh month, of course also without anaesthesia, and as punishment after this agonizing procedure, she was sent to a peat camp four days later. She worked in the water up to her hips for about three weeks; deathly ill, with a fever of 41 degrees, she was returned to the ghetto. She miraculously recovered after three months of severe sickness; however, the now 29-year-old woman will never be able to conceive children again; a bleeding fibroid and injury to important glands were the results of this crude operation. This was only one of many.

Incidentally, people who were not fully fit for work were admitted to the military hospital, where they usually "died" after only a few hours. Young girls who suffered nervous breakdowns because of menstrual disorders or mental anguish, and who were admitted to the military hospital, were very often also injected into the afterlife. The commandant not only ordered all these things, no, but he also loved to be an eyewitness to everything.

All those who were assigned to work were happy, since outside the ghetto there was the possibility of finding something to eat for themselves and their relatives. There were good squads where you got food and were not beaten, these mainly with the German Wehrmacht. Cleaning the tracks and rail spikes on the Latvian railroad was also a popular job, as you could trade clothes, linen, etc. for food with the Latvian population there. Many of us had found useable things in the ghetto, and there was also a clothing store from which we occasionally received something. Our belongings had already been taken from us on arrival, except for what we wore on our bodies. Most of us had put on three or four layers of clothes when we left, and now in the ghetto we exchanged our extra clothes for food.

"Bartering is punishable by death!" was written on every house, on every fence, but no prohibition prevented the hungry, and very many were lucky enough not to be noticed during the evening inspections when entering the ghetto. But if the commandant himself checked, then there were hailstones of beatings and death sentences, which the commandant always carried out himself. With an ironic grin he led the men and women to the cemetery himself, and there he executed them by shooting them in the neck, after the victims had removed their outer garments and knelt with their backs to him. Moreover, every Saturday was court day, and we were horrified when we returned from the work detail to the ghetto and were led past the Galgenberg (gallows hill). People were often hanged for trivial things, for a pack of cigarettes, for example. Every one of us who didn't look up at the gallows during the march past got a blow under the chin from the SS guards, so that we were forced to look up.

The commandant appointed a Jew, who had a large family, as executioner. If he refused, the whole family would be shot, and so the unfortunate man complied. In this way, pictures were also taken in the German illustrated newspapers, which we happened to get hold of later, with the caption "So richten Juden Juden" ("This is how Jews judge Jews"), because pictures were taken of all the executions.

SS Squads

Many Jews who worked at any of the SS offices lost their lives. Mostly there were stores in which food, smoked goods and other things were stored, because the SS was generously supplied. They were swimming in butter, meat, fat, delicacies, tobacco, and sweets. I myself worked for some time in an SS Kommando (squad) where they provided two large geese fried in butter for six SS men at one meal. They lived, as they say, like maggots in bacon, away from the front and danger. They left the glory of heroic death to the Wehrmacht soldiers, in exchange for the danger of the Racial Dishonour Paragraph of the Nuremberg Laws.

There were many beautiful young girls and women among the Jews. At first, only such girls were chosen for the SS squads. There were even squads for which the commandant expressly requested only beautiful girls. Some girls were even requested by name. Since the SS lived safely behind the front in paradise, and had an abundance of food, drink, and tobacco, they had to be provided with an outlet so that, as the Westphalians say, the oats did not sting them too much. The racial paragraph, on the basis of which, thousands of people populated the penitentiaries and concentration camps in Germany, was tacitly suspended, and beautiful young Jewish women had to replace racially pure relationships for the SS. Everywhere, commanders set a "good example" for their crews. The SS sweethearts were often replaced, sometimes they were given a good work placement, sometimes they were sent to some barracks camp, never to be seen again.

Again and again, I must point out that, in the SS, theory and practice were two different things. The guards and foremen in the Jewish camps were made up of felons and street thugs with criminal records from the German penitentiaries, who appeared to us like demigods and often behaved even worse than the SS. Two of these individuals once got into a fight over a half-Jewish woman from the camp. (It was at the company Beton- und Monierbau in Riga.) The girl was immediately shot by the SS, the two kapos (foremen) went unpunished. This is just a small example of how it was in the SS squads: In one kommando (squad), food and some cigarettes had disappeared. Without investigation, every seventh man was taken from the squad, put into a bunker, and shot after three days. This is easy to write, but the amount of suffering the death of these fourteen young people in the ghetto caused is indescribable.

At the Waffen-SS in Riga, there was a cleaning detachment to which I was also assigned. There were accommodation rooms for the SS and the Wehrmacht. However, the SS rooms were separate from those of the Wehrmacht, which we also had to clean. Shortly after the big action in the Warsaw Ghetto had been carried out, the murderers of Warsaw came to our quarters. Their uniforms were those of the Feldgendarmerie (military police). A head constable from Westphalia approached me and asked if I was not also from Westphalia. In the course of the conversation, he said to me: "Whatever the outcome of the war, I can no longer live. If we lose the war, I will not be able to return to Germany, since we have been working as execution troops in occupied foreign countries on the orders of the SS, into which we have been taken, and everyone there would then rightly call us murderers. If we win the war, I will not be able to get rid of the death cries of the approximately 65,000 murdered people from the Warsaw Ghetto. Every night I hear the whimpering of those burned alive, I see the distorted faces of the slain, the bodies of men, women and children torn apart by hand grenades. I cannot live any longer." The next morning, we found him hanged from the window beam of an empty room.

Suicide Missions

At the beginning of April 1942, ice and snow had not yet melted, a special squad of about 40 young, strong men was requested by the commandant. This squad called itself Krause I. Equipped with a blanket and rations for one day, these men, mostly young married men, went out. In vain, the women waited day after day for the men; they remained missing. At last, after about four months, some were brought back to the camp almost dying. These men were emaciated to skeletons, their bodies covered with sickening, festering sores, most of them mentally unwell. They had had to do terrible work on corpses, probably from lost transports. Poorly fed, maltreated daily, they slept at night in the damp cellar rooms of the Gestapo in the central prison in Riga on bare stone floors, 40 men to a cell that might have been enough for ten people at most. This cell was filled with the beastly stench of the excrement buckets and the festering wounds of the sick. It was hardly possible to carry out the dead, as the men were driven to work as early as 4 o'clock in the morning. One of the survivors, Kurt Meier from Witten, related that hunger and cold there had turned them almost all into animals, and one had waited for the other to die so that he could take possession of the remaining clothes, which were totally ragged. Moreover, these men had been brought to the verge of insanity by beatings and sadistic tortures. Starvation, typhus, and dysentery broke out, and without medical help or care, all but seven of these people perished. Of these seven, three died of exhaustion, as help came too late for them.

From all such suicide missions, people did not come back, were tortured to death, or shot as soon as they were no longer needed. The Jungfernhof was also a concentration camp, where the Oberscharführer (SS Staff Sergeant) Mörder (Murderer) Seekt was the commandant. He too was a paragon of sadism and perversity. Whole transports from southern Germany came to the Jungfernhof. From there, too, hundreds of people, elderly men and women, also children, were shipped to Dünamünde. Execution after execution took place there. A special pleasure of the commandant was immediately to shoot elderly men who came into the barracks to get warm. The racial defilement paragraph was, of course, suspended here as well. Pretty young girls served as pastimes for him and his friends. Now that he was satiated with everything, he himself put couples together whose most intimate cohabitation he watched closely. Mostly, he gave some strange girl to a young man whose wife or girlfriend had not come with him to Jungfernhof. It was not enough for these beasts of men to torture and kill people, to tear families apart, they also turned our young girls and women into sluts, merely for their own thrills.

The ghetto is dissolved

By order of the Berlin Nazi government, the ghetto was to be dissolved with immediate effect. In the course of time, so-called central workshops had been established in the ghetto itself, which worked partly for the SS and the Wehrmacht and partly for the inmates of the ghetto. These workshops were transferred to the Straßenhof, a concentration camp near Riga. In total, the camp contained 1500 people, of whom perhaps a quarter survived. Hans Bruhns, supposedly a political prisoner, but a human abuser and unimaginable brute, was the camp elder in the Straßenhof, other prisoners and street thugs with criminal records were the kapos (overseers). Maltreatment was the order of the day there.

In addition, a system of favouritism had emerged there. The camp elder's sweetheart was a Polish Jewess. Needless to say, she and her circle of relatives and acquaintances were doing very well. In this camp, too, death sentences were imposed for minor offences and actions were taken to decimate the camp. For example, all people over 30 years of age were sent away at the end, to where, nobody knows to this day. I myself was later in the Stutthof concentration camp with people from Straßenhof who reported terrible things from there. Deportation to the evil Kaiserwald concentration camp preceded the dissolution of the ghetto. Everyone who was to be sent there was gripped by an insane fear, for we had seen enough of the wretched figures in the ghetto who had returned from there unable to work, their bodies and souls shattered.

All peat camps were dissolved, and their inmates were also sent to the Kaiserwald. The Kaiserwald concentration camp near Riga. Our first camp elder was Reinhold Rosenmeyer, a beer hall owner from Hanover who had been sentenced to life in prison for double murder. He loved women and booze; he kept a harem of pretty Jewish women who took turns spending the nights with him. Apart from that, he did not behave badly towards the prisoners. The SS were not interested in his womanising, but they were interested in his humane behaviour to the camp inmates, and so he was transferred to the Straßenhof camp, and the camp elder there, Hans Bruhns, took over the Kaiserwald camp as camp elder. He brought his sweetheart, who was already, as mentioned, a characterless Polish Jewess, with him. This Hans Bruhns, as I have already said, wanted to be considered a political prisoner. But we all assumed that he was a professional criminal, since almost all political prisoners were not bad to the camp inmates. He, however, was an outstanding abuser of human life. For the most trivial offences, he beat men half to death, slapped women at every opportunity, and thus very quickly made a good name for himself among the SS. Besides him there was Hannes Filsinger, also a career criminal, who led the Luftpark I column. He wasn't one of the worst, but he, too, hit ruthlessly wherever he could. Hannes and Bernd were also two professional criminals, whose surnames I do not know, who both supervised the Spilve (airport) marching column.

If I speak of them as relatively decent, then that's only because punches, kicks and slaps were no longer perceived by us as maltreatment. The leader of the work detail was the professional criminal Schlüter, and he, too, was no different from the others mentioned above. Then there was a political prisoner, Hans Marr from Düsseldorf, who was not as crude as the others, but who had already been infected by them. The worst one was Mister X, also a professional criminal, a beautiful predator, well-groomed, elegant. He was the international con man and car thief Xaver Abel. I have my daughter Edith to thank for the recollections of the Kaiserwald concentration camp; she spent a year and a half there and witnessed everything at close quarters. She was the head nurse in charge of the prisoners' hospital. Above the gate of Kaiserwald, as in all concentration camps, was written invisibly: "Whoever enters here, leaves all hope behind!"

That's what we thought, too, when it was said that all peat detachments would be disbanded and shipped to Kaiserwald. We arrived, about 200 men and women, at nightfall in Kaiserwald, from the peat camp Olaine. The SS with their henchmen, felons, pimps, etc from German penitentiaries, literally beat us down from the cars. Indiscriminate blows struck our faces and bodies, a small taste of what awaited us. Three times that evening we were herded with blows from one part of the camp to another for roll call and then locked in a barrack with the men for the night.

Our direct superiors were, as I have already said, felons and pimps from German penitentiaries and harlots who had become criminals. To some extent these people, who for years had been regarded as pariahs, became sadists when thousands of defenceless people were handed over to them, for better or worse. We often saw men separated from us by barbed wire beaten by these beasts until they collapsed covered in blood. I myself frequently bandaged such unfortunates. Many of those who did not die as a result of the maltreatment remained broken men for the rest of their lives. Many prisoners were permanently deprived of their manhood by kicks in the abdomen and the resulting complications and operations. Likewise, many of the surviving women will remain childless for the future, because organic disorders were caused by the many abortions which had to be performed as a consequence of forced or voluntary sex with SS men or criminals.

Mister X was immensely strong, as the SS executioners ate and drank just as well as their masters. He was the most feared executioner in the camp. He beat the strongest men to the ground with his fist, often without any cause. He stalked around everyone like a predator, so that some were down before they knew what was happening to them. He had many people on his conscience. This beast's Achilles' heel was young and pretty girls and women: he wanted them for himself and brought them food and clothes. On the other hand, older women who were no longer eligible for this special use by the SS and their henchmen had to do hard labour, during which they were often maltreated without pity. The SS were only interested in the violation of the "racial defilement paragraph" of the Nuremberg Laws to the extent that the foremen did not get in their way. They were more interested in the fact that, in their opinion, the criminals were not yet crude enough towards us women. That is why they sent for criminal whores from penitentiaries and workhouses as our superiors. Of course, there were also so-called "Blitzmädel" (female soldiers) supervisors in the camp; they beat us just as mercilessly as the sluts and looted every transport that arrived. The older and less charming our female "superiors" were, the meaner and more sadistically they behaved.

I do not want to withhold one interlude. The first criminal importation of prostitutes from Germany amounted to 40 of these splendid specimens, who were of course housed in the women's camp, but unofficially slept with the kapos (overseers) in the men's camp. On the very first evening, the women moved out. The SS checked the women's barracks; 32 of our new superiors were missing. The SS went looking for them. What happened? As soon as the kapos heard about the raid, they put their naked wives in the bunks with the Jewish men. SS-Commander Sauer, however, knew immediately what was going on and acted accordingly. Now they were still looking for the last ten women, and lo and behold, they had been hidden naked by our convicts in the 500 litre cooking kettles in the prisoners' kitchen and the lids had been closed. When they crawled out, their hair was cut off as punishment, but that did not help either, for the very next evening they were back in the men's camp. During the night, when the peat squads were brought in, these sluts took our sturdiest men out of the common barracks and into their beds. Those who refused would be subdued with blows and threats.

The next morning, we were led to delousing, to speak in camp jargon, "gefilzt", that is, everything we owned was taken from us, we went to delousing literally naked. Afterwards we were "clothed". Of course, everything was done with shouting, scolding and beatings in the presence of the SS and their henchmen. Then one by one we were given clothes. We were thrown a piece of clothing at random, whether it was too long, too short, too tight, or too loose, it made no difference. When we were dressed, we looked as if we had been dressed for a rag ball. Every request for a suitable garment was met with scolding and slapping. We looked at each other. Tall women wore outer garments that looked like dancing skirts, from which the linen showed; short ones had their dresses hanging down to the ground, the sleeves over the tips of their fingers. A procession of sad, degraded women dispersed like whipped dogs to the various blocks. The next morning, we were assigned to the various work detachments. For two weeks we had to work hard in the bitterest cold, without coats, in the outlying squads under the supervision of the criminals, against whose whims we were defenceless.

Some small excerpts from the squads

The Lufttanklager (air fuel depot) was a detachment led by Hans Marr, a political prisoner, a journalist from Düsseldorf. I mention him because he was one of the few who did not beat the prisoners, but what was strange to us was that every little thing that came out of this detachment came to the ears of the SS, that this detachment was always confiscated of everything that people brought into the camp, and in the camp, there was a beating and arrest for it. Hans Marr was quite a mystery to us. Perhaps we were mistaken about him, but we were suspicious, knowing that all the criminals and prostitutes had only become free by promising to carry out all the orders of the SS ruthlessly.

The men's camp was separated from the women's camp by a double barbed-wire fence, and we had to watch as our men, when they returned from the work detail tired, hungry, and beaten up, had to perform heavy, often senseless work after work, with beatings and torture of all kinds. Some of them collapsed, but boot kicks and buckets of cold water served as a means of resuscitation for the horrible torturers. Many men fell ill and died as a result of severe overwork, which their bodies, weakened by hunger, cold, and mental suffering, could not endure. A popular "job-creation method" of the SS was to have the prisoners carry stones from one side of the camp to the other. Back and forth, loading and unloading, with the followers of Hitler using rubber truncheons as a means of propulsion. Every evening, when the prisoners entered the camp, those who had come from the outside squads were checked. If anything was found, the most severe punishment was imprisonment in the bunker without food.

Another punishment for minor transgressions was 25 lashes. The men or women were strapped to a trestle, and usually five SS men each gave five lashes, probably so that the blows would be strong enough. In addition, in winter they were doused with cold water, a punishment that was usually applied only to men. Often those who had been doused were left outside until the water froze, then brought in and thawed out. If you recovered after this procedure, permanent organic damage usually remained. Some of the tuberculosis cases in the camps probably date from such treatments. During the above-mentioned draconian treatment, it often happened that the inmates dropped dead after a short time. One of the many ways of making the already difficult life of the concentration camp inmates even worse, was to get the prisoners out of their bunks at night. As they were, in their shirts or naked, they had to stand on the roll call square for several hours.

Nutritional and hospital conditions

The Kaiserwaldspital was the collective hospital for a whole series of camps. Mühlgraben, Straßenhof, Lenta, and Jungfernhof all sent their sick to us in the military hospital. Since I worked in the hospital, I witnessed everything. The mortality rate in the Kaiserwaldspital was very high, especially when a typhus epidemic broke out in our hospital. Our chief physician was SS-Oberscharführer (SS Staff Sergeant) Wiesener; he was superseded by the camp physician SS-Sturmbannführer (SS Major) Dr Krebsbach. Both were typical Nazi doctors. We the prisoners who worked as doctors, nurses and orderlies, were left in charge of the military hospital. The sick, emaciated almost to skeletons, came to us from all the camps. Although we did what we could, including collecting food from all the prisoners or organising it from the SS kitchen, we often failed to keep the sick alive, since even for them only the general camp ration was available. As in almost all camps, dysentery, the main disease of the prisoners, prevailed in our camp. This disease wreaked frightful havoc. Soiled all over and emaciated to the point of skeletons, its victims could be seen creeping like ghosts through the camp, over and over again making their way to the latrine, wrapped in their grey sleeping blanket.

The hospital conditions in the camp were such that most were insanely afraid of being admitted, not because of the care and treatment there, but because of the actions to which those who did not recover quickly enough were subjected. The SS demanded adamantly that the prisoners who had to do medical service obey all orders. Although we said yes to everything, we did what we thought was right as far as we could. No patient was allowed to stay in the hospital longer than 21 days. The 21st day was the deadline for reporting to the commandant's office.

Of course, none of us prisoners made a report, but the SS held inspections and even wrote down the sick whose time had expired. Often, we were given "twenty-five" for our high-handed actions; but we were already used to the beatings, and we succeeded in snatching many a sick person from the clutches of the SS murderers. Our lot was not an easy one either; even if we did not have to do the hard work outside in the wind and weather, our nerves were tested to a great extent by our work. Many broken and moribund people came to us - the only possibility was to make their last days a little easier. For example, all the sick people who were transferred to us from the Straßenhof camp were death candidates.

Only those who had to watch and participate in these things on a daily basis know what we felt when the eyes of the death row inmates looked at us and begged for their miserable little bit of life. The medical personnel were strictly supervised by the SS as to whether or not they stopped their work on the sick. We were ruthlessly beaten for every little misdemeanour, for example if a sick person's blanket slipped a little or was not completely smooth. In most cases, the punishment was dished out publicly during roll call. Very often we changed the date of admission of the sick because the SS were much too indifferent to the prisoners to take a closer look at them, and so we often succeeded in saving people. There were very frequent "actions". Then the military hospitals were completely emptied. Where the sick were taken, we do not know, only that no one ever returned. The actions by which the sick and weak were removed from the camp were called "Himmelsfahrtskommandos" (ascension to Heaven squads).

Among other things, I just want to report on the fate of the two beautiful sisters Annemarie and Margit Zorek from Gelsenkirchen. They had already been cured of typhoid fever and were only waiting in the military hospital for their last blood test when they too were designated for action. They cried and screamed terribly, because they did not want to die. I kept them hidden in the camp for half a day, but then an SS man discovered them and, since the others had already been taken away, they were taken away in a special car, to where, no one knows.

Methods of death such as shooting and hanging were commonplace, as was beating to death, but towards the end of 1943 a new method of death emerged, devised by a particularly resourceful sadist: drowning prisoners in the latrine, one of the most horrible forms of torture, which can only be described as the spawn of a hellish fantasy. The perpetrators were the felons and criminal pimps from German and Latvian penitentiaries. Barrack clearing was the order of the day. If it was a matter of younger people and skilled workers, you could count on them staying alive for the time being, but if old, weak, and sick people were taken, everyone already knew what was going on.

On 2nd November 1943, the first children's action took place here, to which all children up to twelve years of age fell victim. They were loaded into open wagons in the bitterest cold, supposedly to be sent to a German children's home. Today we rightly ask: What happened to these children? Is what the Latvian railwaymen later told us really true, that the trains with children, the old, the weak, and the sick were driven back and forth on branch lines, of course with the wagon doors closed, until they all starved and froze to death? We never heard from these children again, not even from the last remaining children of the Eastern camps at that time, who were transported away from the Kaiserwald in a collective transport on 12th March 1944. Moreover, on the same day there was another action against the older people from the various camps, who arrived at the Kaiserwald camp in the evening, spent the whole night on the roll call square, and in the morning, together with those who had been selected in our camp, were transported away, as always with an unknown destination.

Base Squad

If one of the camp inmates in the eastern camps was guilty of something, and they wanted to make use of his labour before he was killed, he was sent by the SS to so-called base squads. Such squads were responsible for clearing up the area near the front, for searching for mines, and so on. A great many men and women were sent out, who were then killed after completing this work. There was never a sign of life from any of these people in the camp. Everything in the camp was based on bestiality. If a prisoner died in the precinct, the Kommandantur (headquarters) had of course to be notified immediately, and after only a few minutes a special dental technician of the SS appeared, who broke out existing gold teeth and bridges from the still warm corpses. Horror sometimes overcame me at all that was taking place. When a person had died, the naked corpses were grabbed by the hands and feet and carried out of the barracks like a sack, thrown into an empty pigsty until a truckload had been assembled, and then they were taken away to be burned or buried in a mass grave. The SS did not provide so much as a paper sack to cover the nakedness of the corpses.

The examinations when new transports arrived were also a chapter in themselves. I still remember very well the transports from the ghettos of Kowno, Schaulen and Wilna. These men and women still had a lot of money and precious jewellery with them, since the Gestapo had not yet strip-searched them when they were transported out of the ghetto. Where money was found on the men, the SS and their helpers usually maltreated them terribly, and some were beaten to death. The women were even subjected to gynaecological examinations, which a Jewish prisoner doctor had to perform in the presence of the SS and the kapos. If anything was found during this examination, the women were mercilessly given 25 lashes. All civilian clothes were taken away and the "zebra costumes" known to everyone were put on. When undressing, when bathing, when dressing, they were always beaten. In addition to all this, there was the mental suffering, which the new arrivals felt much more strongly than us, who had already become jaded in the course of time. I forgot to write that at that time the women's hair was already closely shaved, whereas the men's hair was allowed to grow uninhibited except for an "Avus strip" that was shaved out in machine width from the forehead to the nape of the neck, so that the men looked like Struwelpeter (hairy Peter).

Later there were frequent air raid alarms in the Kaiserwald camp. Then we were locked into our barracks, although the fuel depot of the German Air Force was hardly 200 meters away from the camp. Similarly, when the clothing store caught fire, we were locked in our barracks, and we were only allowed to leave the barracks after the roof trusses of the two nearest men's barracks were already ablaze. During the first big bombing raid on Riga, a great many of those locked in lost their nerve, so that weeping and screaming could be heard outside. After the all-clear had been sounded, the SS gave them a beating for it.

As the front drew ever closer, there were renewed roll calls, and the sick and weak were sorted out. Those selected from us were joined by transports from the other camps, and again an immense number of people were sent into the unknown. Then a large transport was assembled, destined for the infernal camp of Stutthof near Danzig, and I was sent along with it. At that time, however, we did not know where we were going. We had only been told that we were being transported to Germany for work. On the ship I happened to meet my mother, from who I had been separated for almost two years. All in all, I think I can say that more than 10,000 people died in Riga as a result of death sentences, suicide squads, actions and poor rations and treatment.

The action of 10th October 1943

On 10th October 1943, the entire ghetto was surrounded by SS with machine guns as early as 4 am. Only the work detachments were allowed to leave the ghetto. At the gates of the ghetto, in addition to our ghetto commander and his staff, the notorious Major Lange had also arrived. When we saw the bloodhound of Latvia (as Dr Lange was called), all hope left us. We already knew that more murder was to be carried out, only who would be affected this time remained to be seen. Would it be the Latvian Jews, whose camp was opposite us, or our relatives? It was already leaking out that 40 of the youngest, most handsome, and most intelligent men of the Latvian ghetto had been taken to the Kommandantur (headquarters) the night before, and that all the Latvian men, half undressed, just as they had been taken from their beds, were standing in front of their apartments with their hands up, guarded by SS guards.

Weapons were reportedly found buried in the Latvian ghetto. Many Latvian men were kept in the ghetto that morning. The work detachments set off for work pale as death and trembling with agitation, not knowing what calamity was once again looming over us. When we returned after twelve hours of terrible inner torment, the ghetto lay dead silent. On Blechplatz, the roll call and assembly point of the ghetto, the SS had driven these 40 young Jews into machine-gun fire with butt blows and rubber truncheons.

Many of them defended themselves with naked fists against the armed SS, especially the representatives of the Jewish ghetto police, Iska Back, Tolja Nathan and Boris Lifschitz. These three knocked down a number of SS men until they themselves sank to the ground, pierced by many bullets. The men who later had to dig the mass grave for the 40 victims told us that several of the boys had been riddled like sieves by machine-gun bullets. The photographs taken by the SS during this action appeared in Germany with the caption "This is how the SS puts down an uprising in the ghetto".

The paranoia of the physically small, puny commander Karl Wilhelm Krause made him see ghosts in broad daylight, and it was only because of his persecution mania that these 40 young men also had to die. One of them managed to escape the bloodbath wounded. They searched for him, and the commandant himself placed him in a remote part of the ghetto. Tolya Nathan, for he was the one in question, called out to him: "You dog, you can shoot me, but first I will tell you what I think of you. You coward, you are the biggest pig on God's earth. You took all our women and girls you liked for yourself, you killed hundreds of people with your own hands, and you enriched yourself with the property of these murdered Jews. You also took my girl by force, and I don't know where she is, perhaps you have already killed her too. But today I tell you, you will perish miserably and with you the whole lying and rotten Nazi dictatorship. So, now you can shoot me."

The commander stood green and pale, frozen like a pillar of salt. Suddenly, however, his face distorted with rage. He shot like a madman at the defenceless, already wounded man, who finally, pierced by 32 shots, covered in blood, collapsed lifeless. Hundreds of Latvian citizens witnessed what was happening on the street, through the ghetto fence. They too were horrified by so much brutality. From them we later received an account of this event. Enraged by this moral defeat, the SS decided to take hostages, and so about 350 more people were taken as hostages to the central prison. They were never heard from again. Our mental depression had not yet left us when the last harbinger of the dissolution of the ghetto came with the action of 2nd November 1943. Some of the squads still went out to work. All the others had already been dissolved. At 6:45 a.m. came the order from the Kommandantur: "All children up to twelve years of age are to present themselves at 7:45 a.m. at the Blechplatz. Warm clothing and a blanket are to be provided." A panic-stricken terror seized the mothers. They had patiently endured everything, hunger, cold, and beatings. Some of their husbands had been murdered, others had died or been deported, older children had been taken to other camps, and now they were to give up their little ones as well. Some of them were on the verge of insanity at that time. Nothing helped, the SS demanded the children.

I too had adopted a little golden blonde adorable girl when she was 16 months old. The child's father had died in Salas Pils, and the mother had lost her mind. She had just turned three in October. I had to take this bright child to Blechplatz, the place from which the blood of 10th October had not yet washed away. With her little bag in her hand, she walked beside me, pale as death, repeating, "Mummy, you are going too, aren't you?" My heart bled, for we knew what was in store for the children. By now Blechplatz was full of children, all of whom knew that they were facing a terrible fate. Mothers and grandmothers begged the SS to allow them to accompany the children, and as long as they were not skilled workers, the biological mothers were allowed to go along.

In the meantime, the SS searched the houses, and all the elderly and weaker people were taken to Blechplatz. The military hospital was broken up, and the seriously ill were pushed onto the trucks on stretchers, including some with very recent serious operations. One woman escaped, the staples from a serious abdominal operation still in her wound. She saved herself from this action, only to perish a few weeks later from sepsis. Terror gripped the entire ghetto. The screams of the women and children sounded horrible, among the roaring and beating of the SS. It was terrible! Finally, the poor little worms were loaded into a long train at the Shirotawa station, together with the old, the weak and the sick; in freight cars without straw, with only bread rations, in minus 32 degrees. So many people had been singled out that finally only about 1,200 people, mostly skilled workers, remained to be barracked in an "army clothing" camp. When we, a sad lot, went back to our apartments, the German and Latvian SS had completely ransacked them and in part even plundered them. The ghetto had become deadly quiet, all children's laughter had fallen silent. No one knows what happened to the deportees; there were over 2,500 of them.

Army clothing camp Mühlgraben

A few days later those who had remained in the ghetto had to line up with their luggage in the Blechplatz for transport to Mühlgraben. We got into the trucks and were driven to the Kaiserwald concentration camp for inspection. There we were registered, given prisoner numbers - we had already had stars front and back for years. Everything that was still good in the way of laundry and clothing was taken from us. As a bonus, we received beatings and blows. I had blood poisoning in my right hand, a fever of almost 40 degrees, and could hardly bear the pain. Then we saw our men standing opposite, and I saw a man being knocked to the ground three times by one of the criminals. All at once I felt, "your man is being beaten there." Already I was being pushed into the barracks for inspection. I received a blow in the face, but I felt nothing, I was numb. Our suitcases had been taken by trucks to Mühlgraben beforehand, and after we had been registered, we looked forward to the warm clothes and linen we thought were safe. We arrived at Mühlgraben late in the evening, tired from the Kaiserwald. Dead tired we sank down on our straw sacks.

Our awakening was a great shock. Mühlgraben was nothing more than a branch of Kaiserwald, and even there we did not get our suitcases back. The camp elder, the camp police, column leaders and leaders employed in internal service, but above all the SS commander Unteroffizier (Corporal) Müller, a hairdresser from Mülheim (Ruhr), and his helper Saß were the beneficiaries of the clothing store set up from the contents of our suitcases. From Mühlgraben, we were assigned to work in the various departments of the Army Clothing Office. Our division took place in the same manner as we had seen in the Kaiserwald. I was assigned to the "Infantry Barracks" column as a seamstress. The walk from Mühlgraben to the infantry barracks was about three hours. It was interesting how we made the trip. Five hundred people were loaded into a cement barge like precious cattle. Piled up one on top of the other, we rode standing up for three hours, arriving at the work site completely clogged up, so that we were often unable to work for the first few hours. It was the same transportation in the evening. Often it was 10 o'clock before we got back to the camp. Then we had to fetch our soup and bread, so that it was usually midnight before we got to bed, and at 4 o'clock in the morning we were woken up again.

Now something about the camp itself. In Mühlgraben there used to be a factory building belonging to IG-Farben, where ultramarine was produced. Everything there was blue and hazy. Women and men were housed separately, but it was often possible for the women to join the men. The death penalty did not scare us. This camp was still bearable despite the bad food, because the women had the opportunity to see their husbands. When winter's ice and snow came, we were transported to work by freight train. In the mornings, the train often stood on the track for hours. In the evenings, we almost always had to wait for a few hours in the open for the freight train that was intended for us. Many of us fell ill because of the cold and damp, but we were not allowed to stay in the camp until our fever had risen above 38.5 degrees, and so, many illnesses continued until they became chronic. Days of excitement were soon followed by deceptive calm. Our Mühlgraben was a reception camp for army supplies from the East. Wagons full of bloody and torn army clothing came back from the field, which had to be cleaned and reprocessed by us.

The plethora of bloody uniforms told us that the war with the USSR could never be won, despite all the reports of victory. Our hearts slowly began to hope. The more the war with the USSR progressed, the more nervous our tormentors became. One after another, the heads of the army clothing stations and workshops, members of the Wehrmacht who were humane to us prisoners, were replaced by party comrades who took the same attitude towards the concentration camp prisoners as Hitler, Goebbels, and Himmler. Squad checks followed one after the other, so that it was almost impossible to supplement the meagre concentration camp rations. Unrest gripped the inmates of the camp. The number of cases of illness increased. Those who were ill for a longer period were taken to the main camp at Kaiserwald, mostly never to be seen again. Our camp still included about 25 children who had been hidden during the action of 2nd November. We were all happy about the children's laughter, although many of us had lost our own children. One evening, when we returned from our work details, all the children under 14, including those who had already been called up for work, had been taken away by the SS.

Meanwhile, the Nazi acolytes of Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels, and their consorts had devised a new cruelty in the ghetto. Whether the sight of our women and girls aroused the sexual desire of the overfed SS too much, or did they want, as they used to say, to make us "parasites" recognisable? In short, all Jewish women had their hair closely cut, just like in the Kaiserwald. Our heads looked as if they had been shaved, we shook with horror when we looked at one another, we no longer recognised each other, we were so disfigured.

A black Sunday in Mühlgraben

The commandant had ordered, "No one is to leave the building, a punitive action will be taken." "Something has happened in the gas hall," they whispered to each other. Already we saw the victims coming. They were walking two by two, each with a large board loaded with logs weighing about two hundredweight hanging around their necks. This had to be carried 200 to 250 metres further, at a gallop (it was summer, about 30 degrees C). The commander and two assistants drove the people with rubber truncheons; there were 19 men and one woman. Three wagons of wood had to be unloaded in this way.

After a short time, the victims collapsed. They were kicked and doused with cold water until they got up again. Frau Käthe Ehrlich, a beautiful, tall, blond Viennese woman, was particularly targeted by the commandant. He beat and drove her until she collapsed bleeding, and then he beat her some more, until a doctor and nurse arrived and took the unfortunate woman to the military hospital. A Viennese philologist, whose name escapes me, who had a damaged lung, got a rush of blood, and also collapsed. He too was kicked and beaten when he was already lying on the ground. He later perished of physical weakness in another camp. All 29 delinquents were beaten until they needed hospitalisation. The reason given was that Wehrmacht property had been stolen from the gas hall, and since the culprit had not been found, an example was made of the gas hall workers. One morning, when all the squads were about to go out to work, they were picked out. About 200 people were chosen and sent to an army clothing office supposedly in Germany. The name of the camp also escapes me, but it was in West Prussia. Later we met some of the people again in Stutthof.

A medical commission in the camp

Our men stood completely naked in the yard. Those who were physically not up to it or had a hernia were picked out and immediately loaded onto trucks. Then it was the turn of us women. All of us who looked old and weak were sorted out and sent off, never to be seen again. We heard later that this action had been carried out in all the camps under the control of Kaiserwald.

In the meantime, a large army fur clothing warehouse had been destroyed by fire. Furs worth millions, which had arrived from Russia as so-called war booty, fell victim to the fire. I forgot to mention that all the senior employees of the SS and Army Clothing had precious fur coats made for themselves and their relatives from these stocks and sent them to Germany. When the Mühlgraben commander went on leave to Mülheim an der Ruhr, he took with him eight large suitcases. Silk dress shirts for himself, silk lingerie, girdles, and bras for the wife. Dresses for women were mass-produced or altered in our workshops. All from the confiscated suitcases of German and Latvian Jews. He also took home watches, jewellery, fountain pens, and miscellaneous items. This non-commissioned officer, who after all had been only a small barber in his homeland, got delusions of grandeur just like the commandant of the ghetto, Karl Wilhelm Krause. Delusions of grandeur were a typical National Socialist disease, the main carriers of which were Hitler and his adjunct Goebbels.

Every Saturday after the work detachments returned to the camp, a prisoner count took place. Woe betide anyone who escaped. Then there were draconian punishments, mostly the reduction of the already meagre food rations and the dispatch of hostages to the Kaiserwald. A terrible thing to hear was also being sent to so-called outpost squads. We thought these squads were death squads because no one ever came back from there. "Sunday will be free, there will be no count!" That's what they said one Saturday night. A free Sunday! We were happy to be able to sleep until 7 a.m., since every morning we had to wake up at 4 a.m. and report to the work detail at 5 a.m.

The next morning, we were woken up at 6 o'clock. Everyone was herded out by the police. The thoughtful ones said, "shipping out," dressed and took the necessities with them. The carefree said "count only" and just hung their coats around themselves. I was one of the former; I had long before made myself a large shoulder bag of canvas, and I took my belongings with me in it. When we saw SS outside, we knew enough. In the meantime, the names of the men were read out. Those called up had to line up separately. After the men it was the turn of the women. I was one of those who had not been called up. My husband was among them, and I asked the commandant to take me with him. After much pleading, he exchanged me for a young girl who wanted to stay with her aunt. The chosen ones were led into the gas chamber, and felons and prostitutes from the Kaiserwald took everything we had with us. We also had to take off our overcoats and outer garments, and in exchange were given new blue and grey striped convict garb, which later had our prisoner number marked on it. I received the number 51566.

Our men had been frisked, changed, and had already been loaded into a ship. We, like them, received camp rations for three days and were loaded onto the same ship; we in the front of the ship, the men in the back. It was impossible to see or speak to each other. We went by ship as far as Riga Bay, where there was a huge ship, which we were to be loaded into. We saw several steamships pass us by, with almost exclusively by young people on board, who were accompanied not only by the SS, but also by the camp overseers, camp and block elders. We already knew some of these SS henchmen, and thus knew that the Kaiserwald and Straßenhof concentration camps had also sent their people. I now had a faint hope of finding my child, and when I asked the notorious criminal X, whether the Kaiserwald transport included my daughter, who had worked in the Kaiserwald hospital, he told me: "No". Sadly, I climbed into the lowest room of the horribly dirty ship, found myself a spot (a bunk for three to four people) and lay down.

How long I had lain brooding, I don't know, because the ship was already sailing. Suddenly I jumped out of the bunk as if electrified. The voice was that of my daughter, and when I looked for her, I saw her coming down the ship's stairs in a white coat. Neither of us could speak, we just held each other tightly after more than two years of separation. Now it was easier for me, I had one of my three children with me again. We travelled on the steamer for four days, crammed together like herrings, with the anxious question in our hearts: What will happen now? We had been told in Mühlgraben that we would be sent to work in Germany together with our men, but the SS had already lied to us many times. At last, we entered Danzig (now Gdansk) Bay, where we were unloaded. Now we would finally see our men, who had lain in another part of the ship during the trip, guarded by SS just as we had been. We were allowed to lie down in a large meadow, the women on the right and the men on the left, guarded again, of course, by the SS, who were supposed to prevent any approach with repeated blows. In spite of everything, we found a few seconds to exchange a kind word, to offer some consolation. Our men looked terrible in their convict costumes, with their flat, peakless white-and-blue caps.

Deportation to the extermination camp Stutthof

The rest of the rations taken from the camp were distributed, and then we were loaded into closed barges, which were otherwise used for coal, lime, cement, or stones. This loading meant unspeakable cruelty. The hatches were opened, and the SS drove us into the barges, two to three metres deep into the hold, without light and without air. Many of us fell from the ladders as we were forced to hurry, and everything happened without a sound, because the SS beat us at the slightest word. The barges were so crowded that one could hardly stand. It was July and suffocatingly hot. So we went without light and air from evening until early morning. Later we heard that the men had had it even worse.

More dead than alive we arrived. The SS received us with screams and blows, and then we went to Stutthof, a distance of about ten kilometres. When we German Jews saw the clean little houses in the small towns around Danzig, a hope glowed in our hearts again, we whispered to each other: "Now we're in Germany, maybe it'll be better now, maybe the cruelties will stop here. Surely they won't dare to harass and murder concentration camp prisoners for trivial offenses in front of the German people."

Still outside the camp proper, where the barracks were still under construction, we camped on the ground. We were happy that we could wash, that we had clean drinking water. The foremen we met there were very polite to us, and so we waited full of hope to see our men. Hours later, we saw the endless train of our men coming. We were happy, we wanted to wave to them, but we were driven back from the wire by SS guards. We no longer saw our men; we only heard the screams of abuse in the night. We were housed in a stone skeleton with no roof, no floor, no doors, and no windows. The following morning, we were taken to the real Stutthof camp. The gates of hell closed behind us.

Barrack 18a

Each barrack had two parts, part a and part b. Each of these parts was calculated for 250 women. Blocks 18a and 18b accommodated 900 Jewish women each. Even if four people slept in each bunk, there was still insufficient space; packed one on top of the other, we lay on the ground, exposed to the merciless blows and kicks of the block elders. The reception with strap and cane beatings, kicks and slaps gave us a foretaste of what awaited us. There were exemplary washrooms and clean modern toilets, and we were glad that we could at least take a shower every day. But the washrooms and toilets were only open for a very short time. Lenna, our block elder, suggested we crowd into the washrooms because everyone was afraid of getting clothes lice. Head lice did not come to our shorn heads.

Roll call was at 4 o'clock in the morning. There was no time to wash. The roll call had to be completed within three minutes. It did not go off without beatings. A prisoner named Max Mosulf, the executioner at Stutthof, oversaw the Jewish women's barracks. He literally beat us out of our bunks, laughing with scorn and beaming with joy when his blows had been particularly well aimed. The entrance to the barracks was extraordinarily narrow. 900 women pushed out, partly out of fear of M's blows, partly out of concern about being late for roll call. Into this crowd of people, the two block elders, Sch and L, beat with their belts or sticks: They struck with their belts or sticks until the women finally jumped out through the barrack windows. German Jewish women were particularly detested by these three henchmen.

After roll call, which often lasted for hours, we were given coffee and a piece of bread. We had to line up in rows of two, and each pair received a bowl of coffee together. When we fetched the coffee, we were beaten again, and if a woman was clumsy because she was afraid of being beaten, the hot coffee was poured over her. No sooner had one found a place to eat one's bread in peace than it was said again, "Out, roll call!" Standing roll call in the blazing sun, lining up, standing motionless, not being able to do one's business, for the toilets were locked during the day, we stood until noon. Some of us who could no longer bear standing in the burning sun sat down for a moment in the rows of ten, others fainted. At noon, we had to line up again in twos and were again given a bowl of about a litre of soup. Mostly it was cabbage or grain. The soup wasn't too bad, there just should have been more, and we should have been given time to eat it. No sooner had we found a place to eat and settled down, than belts were striking heads and backs again.

Once again, we were beaten out. Those were the first days. For us, who were accustomed to working all day, this hour-long roll call was terrible. Finally, the torture was over, we were allowed to go into the barracks and lie down, after we had received our allotment of bread and a little margarine. Now the misery came again. There was not room for all of us. We pushed and shoved each other on the floor, one kicked the other in the face, one lay on top of the other, and of course sleep was out of the question. If one really did fall asleep, one was very soon rudely awakened by a boot kick, and those lying on the floor were trampled on. Those lying in the bunks in threes or fours were doused with cold water, which some women had to carry in buckets. The front barrack, where our block elders lived, was also very lively during the night. Men went in and out of there all night long.

On the second evening, I volunteered for the night watch, firstly because I could not sleep, and secondly because there was to be a special ration of bread for the night watch. I had another reason. I wanted to get to know the camp properly, since we always hoped to survive it. We were a small circle of socialist women who stuck together as best we could. We wanted to survive the camp to show posterity the brutality, even bestiality, with which the Third Reich was ruled. There were very few German Jewish women in our block, and we were separated from the other blocks by barbed wire. It was forbidden to speak to the inmates of another barrack, but prohibitions concerned us little at that time, and so we learned of the torments of our sisters from the other concentration camps and peat camps. Everywhere it was the same, with small differences. Hunger, beatings, megalomaniac commandants, Jewish commandant- and SS-lovers, mostly forced, criminals and whores everywhere as foremen and superiors, everywhere they called us "You Jewish sows!" and "You filthy beasts!"

A few words about the character of Max M, the executioner of Stutthof

On the third day after our arrival, when the SS with the Blitzmädels (female soldiers) took roll call from all the Jewish barracks, Max M said loudly, so that each of us could hear, to the SS commander, "I don't understand why they provided coal for the Jewish ships, I would have burned the whole herd of pigs in the crematorium with much less coal. That would have been a festival for me." When some of us jerked up in horror, he said, "I can hang them up, pretty, side by side, like birds, well, Commandant, how about that, then we're rid of them?" He really was an executioner; we got proof of that in the next few days, when he hung 60 men side by side.