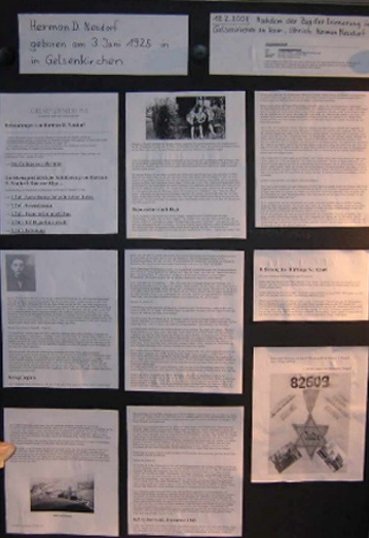

Memoirs of Herman D. Neudorf

Memoirs of Herman D. Neudorf

The memoirs of Herman Neudorf: That was Riga ...

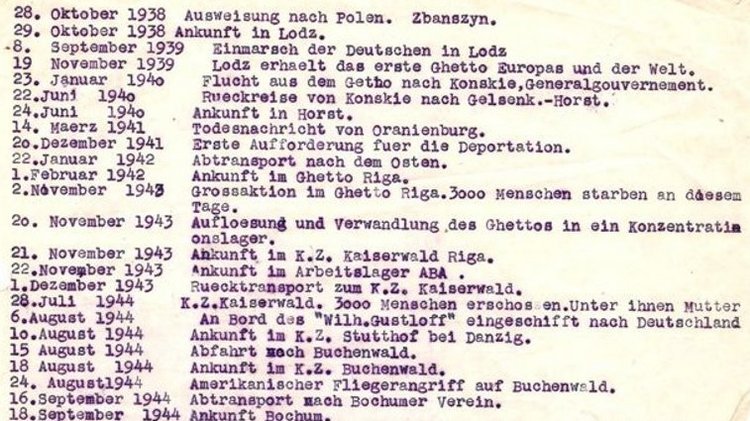

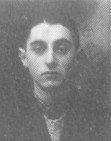

Until 28th October 1938, Herman Neudorf lived with his parents at Markenstrasse 19 in Gelsenkirchen-Horst. The Nazis took him out of school that day and deported him and his mother to the Polish border area. In July 1940, Herman Neudorf was "allowed" to return to Germany. In the meantime, his mother had been moved from the apartment on Markenstrasse to one of the so-called "Jewish houses" in Gelsenkirchen at Markenstrasse 29, where mother and son had to live in one room. His father Simon Neudorf was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp after the German invasion of Poland and murdered there on 14th March 1941.

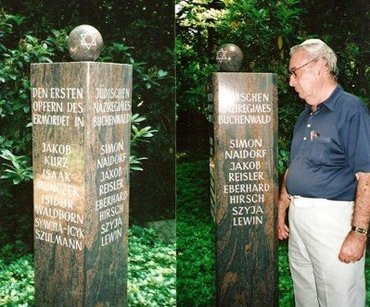

On 27th January 1942, Herman Neudorf and his mother were initially deported to the Riga ghetto. Frieda Neudorf was shot when the Kaiserwald concentration camp (Riga) was dissolved on 28th July 1944. Herman's further path of suffering led to the Kaiserwald concentration camp in Riga, via the Stutthof concentration camp, to the Buchenwald concentration camp. From there to the Buchenwald subcamp at the Bochumer Verein and then back to Buchenwald.

Finally, on 13th April 1945, Herman was liberated by US troops on one of the death marches from Buchenwald. Today he lives in the USA under the name Herman Neudorf. In an email to GELSENZENTRUM e.V. in August 2007, Herman Neudorf wrote: "Often you wonder how you could survive these terrible years at all."

Expulsion of the Polish Jews

"On 28th October 1938, when I was just 13 years old, I was taken out of class by the Gestapo during lessons and put into Gelsenkirchen prison. There I met my mother. From there we were sent to Poland. We had nothing at all with us; my mother had been arrested on the way to the market. Apart from her handbag she had nothing with her. My father had been told that they would only arrest the men - he had received a telephone call from Essen. He had been told that they would only arrest Polish-Jewish men, but that they would leave the women behind. So, he had gone to the Polish Consulate in Düsseldorf to get papers. Because he had disappeared, we were arrested. When he returned, we had already been taken to the German-Polish border.

The Germans had thrown us out and the Poles wouldn't let us in. It was the end of October, it was cold, and we had nothing - no blankets, no coats - nothing. We camped in schools, lay on straw, there was nothing there at all, but a telephone. So, we could call our relatives in Poland - grandfather, grandmother, and aunts. We could tell them where we were. They sent us money for a train ride to come to them. Our relatives took us in at first. We had made contact with my father and towards the end of the year he came to visit us in Poland. His mother had died of natural causes. We went to the funeral, and we were all together again.

But then my father got permission to go back to Germany with my mother to hand over the business, because in the meantime Kristallnacht (the anti-Jewish pogroms of 9th November 1938) had taken place. I think it was February 1939, but there wasn't much left, everything was destroyed. So he went back to liquidate the business for good, and we thought that we could emigrate after that. What made it difficult to emigrate - and especially to emigrate to the United States - was that we fell under the Polish quota, and this Polish quota gave us no chance to immigrate to the United States before 1943 or 1944. We would have gone anywhere else, but we couldn't. Therefore, we had no way of escaping anywhere."

Start of the war

"On 1st September, the war broke out. I was in Lodz, and my father and mother were in Germany. On 2nd or 3rd September, my father was arrested as an enemy alien. He was taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin. So, my mother was alone in Germany and I was in Lodz. As I remember, the Germans marched into Lodz on 8th September. From then on, everything changed dramatically. Now the Jews were fair game. They were picked up, loaded on to trucks and from one hour to the next people didn't know what became of their husbands, fathers, and sons ... Jews were beaten or expelled. Some Poles were happy to take positions from Jews. Jews could be treated however they wanted. But that was only the beginning.

In 1940, I think it was in January, the Germans began to build the first ghetto. That was in Lodz. During that time the name changed from Lodz to Litzmannstadt. I managed to get out of the ghetto the very week they closed it off for good. My aunt and her husband took me in.

With some others, we went by horse and cart to a place called Konskie. That was in the country, it was not as hectic there as in the city. There was no ghetto there yet. I stayed there until June 1940.

"In the meantime, my mother had tried to get permission from the Gestapo for her only son to come back. I don't know why, and I don't know of any other case, but they gave permission for me to come back to Germany from Poland and be reunited with her.

In other words: In Lodz we already had the Yellow Star on our clothes front and back. In Poland we had a white band around our arm with a blue star on it, and now they allow me to ride a German train. To this day it sounds unbelievable: A Jewish boy was allowed to ride back to Germany from Poland with the German troops."

"And I came back to Germany in June 1940. After 'Kristallnacht' my mother had been taken from our apartment at Markenstrasse 19 to a Jewish house at Markenstrasse 29. There I now lived with my mother in one room. At first, we didn't have to wear a star, we could move around freely and go to work.

I worked as a carpenter at the Lohmann company in Essen-Segeroth. There was a Nazi there who often tormented me. From September 1941, all Jews in Germany had to wear the yellow star. When I rode my bicycle from Horst to Essen to work, I left my jacket open, and the wind blew the jacket over so that the star was hidden.

We got mail from my father - once a month he could send a card from the concentration camp. We knew that it was hellish there. But as a child I didn't really know how bad it was. But my father always wrote that he was fine. I wrote to him. And I also wrote to relatives saying that he would get out if we got a visa from some country."

27th January 1942: Deportation to Riga

"On 20th December 1941, we received the first order from the Gestapo, Gelsenkirchen State Police Office: "You are to prepare for transport to the East for work. You are allowed to take 10 RM of luggage with you. You have to pay for your own transportation." So everything that we had laboriously acquired after the anti-Jewish pogroms of 9th November 1938, was to be left behind and given away to the rapacious Nazis!

My mother lay ill. The nerves of a woman so severely tested were failing. It was too much, since the terrible 9th of November... Daily new torments. Made poor overnight, possessions destroyed or stolen. Taken from her husband by force at the outbreak of war. He was, after all, Polish and, above all, Jewish. He was, after all, an enemy of the state. After weeks of waiting for a sign of life, a greeting arrives... From the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. I was in Poland and witnessed the German invasion. So this woman stood alone. Husband and child far away, in the hands of the murderers.

After months of struggle, they managed to get me, their only child, back. The joy of reunion made me forget the suffering a little. At the end of February, Grandma, her mother, died. Shortly after the week of mourning, a letter came from my father. "I am well. I'm in good health. Be strong! Cheer up! See you soon." There was great joy, and I saw my mother laugh again after a long time.

Two days later, the unforgettable 14th of March. Shortly after eight o'clock in the evening the postman rang. A telegram. I receive it at the front door. I quickly opened it, read it, and my eyes widened in horror. I think of mother. I hurry upstairs, step into the room, as white as a sheet. "Who was there?" I could not speak. "What's the matter? What's the matter?" I could only bring myself to say, "Mother, be strong," and handed her the paper. It said, as if in a dream, I spelled it out, "Your husband died today of pulmonary tuberculosis. Ashes to follow." And after these terrible months, deportation. Where will it end?

Preparations were made. Medicines, antifreeze, winter clothing, warm blankets and so on were procured. On 20th January 1942, another letter arrives: "You are to be ready for transport to the East in the next three days." Now the time has come. On 22nd January at 10 o'clock in the morning we were picked up by the Gestapo and loaded into a bus, each with a suitcase. In no time, a number of school children gathered around the vehicle. To their curious question as to where we were going, the Gestapo chauffeur replied: "To a sanatorium for rest and recuperation."

At the assembly point (the exhibition hall at Wildenbruchstrasse), we slept one night on the floor and the next day we were loaded. It was 27th January 1942, but these murderers knew too well where our journey would lead. High snow and about 25 degrees below freezing. The train was ready. Unheated. Three cars were hitched to the end of the train with our suitcases, rations, and kitchen utensils. Then we departed. Doors locked, of course. Before we reached Hanover, we learned that the last cars had "overheated" and had to be unhitched. Now we only had what we were wearing. Six days' journey through East Prussia, Lithuania, and Latvia. Lavatories were clogged, the walls of the compartments were covered with a layer of ice. On 1st February we reached our new home.

The transport stopped at Riga-Skirotava station. SS men in thick fur coats were already waiting for us. They drove us off the train with blows and yelling. Our limbs were still stiff from the cold. We left partly by truck or on foot. About three hours' march. Latvian guards guarded us carefully and tore off good clothes from some of our bodies. A district surrounded by barbed wire appeared. I could make out people with yellow Jewish stars. So this was the Riga Ghetto, which we would all remember forever. Having arrived at the ghetto, I immediately met acquaintances. Jews from all parts of Germany had arrived before us. Transports from Cologne, Düsseldorf, Bielefeld, Kassel, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Berlin, Vienna, and Prague.

By chance, my relatives from Herford and Kassel also came to Riga, so that there was an overjoyed (me) reunion, marred only by the barbed wire. Then quarters were sought. Ten people in one room. Apartments full of vermin. I knew a bug or a louse only from biology lessons in school. First thing the next morning, work detail. 500 men to the port. I volunteered immediately, thinking I'd get something to eat on the job. At six o'clock in the morning pitch dark, minus 30 degrees, surrounded by about 40 SS bandits, we marched to work. Two ships loaded with bales of straw were waiting for us at the harbour. Unloading, hounded by SS and Wehrmacht. There was no finish time. At midnight we dragged ourselves back to the ghetto, broken, frozen and hungry. Now I also knew what starving was.

Thanks to the excellent organisation of the Jewish ghetto leadership, the division of labour gradually became more regulated. Mother became a carer for the Viennese group. She had a difficult but beautiful task and thus became the carer for the Viennese children, sick and old people. My aunt Else worked from morning till night in a sawmill, in order to be able to procure the necessary fuel. Uncle Robert, who was known to the SS as an efficient car mechanic, was separated from his wife and sisters in the very first days and taken out to do locksmith's work in SS workshops, where he also had to live. Of my Kassel relatives, I will mention that Hermann had a good position as an electrician and that Aunt Hedwig was able to care for her boy.

I myself worked as a carpenter, electrician and glazier in the Wehrmacht and thus had the opportunity to provide for my physical well-being. I must now explain. A few days before our arrival, 20,000 Latvian Jews were shot in the ghetto to make room for us newcomers. An old SS method. We now entered their apartments, where we found household goods and clothing still there. To save us from starvation, everything that was not urgently needed was traded to the Latvians for food, that is, by whoever had the opportunity. At my place of work there were a lot of Russian workers, and I became a great "trader".

I learned Russian and a little Latvian, and I threw myself into the business with all my might, knowing that my loved ones would be happy when I got home in the evening. Now came the backlash. "Bartering is punishable by death," you read on every house. Comrades were hanged for half a pound of butter. Strict controls at the gate in the evening. It's no use. Ten are hanged and thousands struggle on to preserve the lives of their families. It went on like this for a year. Then we heard of the glorious defeat at Stalingrad and the mass murder began."

Kaiserwald Concentration Camp, December 1943

"On 2nd September, the first 3,000 go to their deaths, personally selected by the commandant, SS-Obersturmführer (SS Lieutenant) Krause and his adjutant Roschmann from Graz, as well as Unterscharführer (SS Corporal) Schröder from Ginnich. All the children, the sick and the old were taken from us. A truck stopped in front of the hospital and the unsuspecting sick were loaded on like "freight". Now we were only a few. We knew that the ghetto would be dissolved, and a concentration camp would be created. And so it was. The terrible concentration camp Kaiserwald was built in the most beautiful part of Riga. Fortunately, I stayed with Mother. Aunt Else was sent to a factory and had to live there with 3,000 Jewish people. Uncle Robert was still with the SS in the city and had it reasonably good. The Kasselers were taken to the Reichsbahn (railway) to work, after their only child, dear Hans Manfred, succumbed to diphtheria. Poor Aunt Hedwig tried to commit suicide but was saved again. Aunt Rosi succumbed to dysentery. Now the second act.

Long, grey barracks, surrounded by high double barbed wire, that was now my new home. As soon as I arrived, I was separated from my mother. She was sent to the women's camp, and so I could only see her through the fence. All the clothes we wore were taken from us and we were given rags with large white crosses on our backs and chests.

I saw SS guards for the first time. Beasts in uniform, boots, pistol, and whip, that's how they harassed our women, beat and kicked them. Oh, the glorious German woman, the famous German culture!! I can say that the SS women far surpassed the SS men in brutality.

Mother became very ill. Pleurisy. I wasn't allowed to see her. At my new job, a Wehrmacht car repair shop, I stole car parts and sold them to civilians for food. Mother had to live. And God helped her. Those dogs shouldn't have it so easy. Dear Mother got better. Oh, how happy I was, when she could talk through the wire again for the first time! And so the summer came and Russia's Red Army marched forward, we hoped and waited. Kiev, Minsk, and Vilnius were stormed. The name of Latvia is already mentioned in the German news. What will become of us? Will they let us live?

27th July 1944 brought the answer: After the usual evening roll call, the "camp doctor", SS-Sturmbannführer (SS Major) Krebsbach, suddenly arrived with a staff of senior SS officers and inspected everyone thoroughly. The older and poorer looking ones to the right in a barrack manned by guards, the others to the left on the side. Everyone knew, death on the right, temporary life on the left. The barrack was filling up. We had to watch. After the men were finished, he went to the women. The same picture. Those destined for the right were lined up in a column and led into the barracks under the strictest guard. The unfortunate procession passed me, it was dark, and I saw, I could not believe my eyes, my dear mother was among them. I walked as if in a fever. I think I screamed all night. I don't remember. At dawn I tried to get to that death barrack, but the SS guards who had surrounded the building drove me back with blows.

From afar I stopped and stared at the windows. And really, mother had seen me. She asked me, "Where are we going?" I replied, "I'll see you soon." To which she replied, "In heaven?" At that moment, a butt blast from a guard hit me and I rushed away. I never saw her again. Later, when I went to the commandant, SS-Sturmbannführer (SS Major) Sauer, and begged him in my distress to let me be with my mother, he cynically replied that I could go along if I felt like it. Is there now a punishment in the world great enough to do justice to these terrible atrocities?

From that day on, I was alone. In the Strasdenhof camp, where Aunt Else was, everyone over 30 was taken away in the same way. At the Reichsbahn, the same thing happened. Nothing more has been heard of all these poor people to this day. Some of these SS murderers later boasted about their heroic deeds in the Riga Hochwald. Now the situation became critical for us as well. Will we suffer the same fate, man and woman??

On 6th August 1944, after morning chapel, by now already shaven and in striped clothing, half the camp was evacuated. I was among them. The went to the harbour, where we were crammed onto a large ship below deck. At first, we again expected a rogue attack, but when SS and Wehrmacht officers joined us, we felt safe. I do not want to describe the terrible three days on this hellish ship. I'll only mention that some fainted from thirst. Our landing place was Danzig, and from there we went to the Stutthoff concentration camp. There, too, the conditions were terrible. But thank God we stayed there only a few days and were then sent to Germany for work. When the train stopped, we were in Buchenwald, where I was then liberated on 13th April 1945."

The Escape and Happy Liberation of Prisoner No. 82609 of Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Herman Neudorf spent seven years in the hell imagined by the Nazis. Lost his father, mother, relatives, acquaintances, and friends. Now he is free. However, the memories of these terrible times will hold Herman D. Neudorf captive for the rest of his life.

On 10th April 1945, 4,000 prisoners from Buchenwald concentration camp were sent by the SS on a death march that was to lead from Buchenwald to Dachau. Among them was Herman Neudorf. They were eventually liberated by American soldiers near Jena. In an account, Herman Neudorf describes the circumstances of his escape and subsequent liberation.

In the following report dated 20.4.1945, Herman Neudorf wrote down his memories of the death march from Buchenwald concentration camp and his subsequent liberation.

Buchenwald, 20th April 1945

In through the gate,

out through the chimney

(slogan of the SS).

Escaped death.

The escape and happy liberation of prisoner no. 82609 from Buchenwald concentration camp

Monday, 9th April 1945, 8 a.m.

A mood of alarm prevails in the camp. The SS bandits suddenly show feverish activity in packing suitcases. 10,000 prisoners have already left the camp, accompanied by heavily armed SS guards. Where to? Allegedly to Dachau. We suspected something terrible. These murderers, armed to the teeth, will kill these innocent people "by order of the Führer". We are prepared for the worst. Shall we now, at this critical moment, when the liberators are only a few miles away from us, when comrades of the R.A.F. are circling overhead every hour, when we have happily survived these years of suffering and cruelty, become yet more victims of these beasts? Will the victorious Allied armies succeed in being faster than the bullets of these brutes who want to put an end to our lives? The prospects of survival are very bleak, but I don't give up hope yet, maybe I'll have a bit of luck for once....

Tuesday, 10th April 1945, 1 p.m.

From the tower at the gate, the following order comes through the microphone to the camp leadership: "By 4 o'clock, 4,000 people are to be ready for transport on the roll call square." The camp elder and his staff lost their heads, unable to hand over any more of their fellow sufferers to the SS officers. There is not a single person left to be seen, hidden in cellars, pits, boxes, even privy pits, everyone fears for his life.

At 3 p.m. the eerie voice of Hauptscharführer (SS Sergeant Major) HOFSCHULTE sounded again through the loudspeaker: "If the herd of pigs (by this, of course, he meant us) is not in front of me within an hour, we will intervene ourselves." What this "intervene" meant, each of us knew. And once again the camp guard (police) rallied to carry out the terrible order. I, too, was brought out of my beautiful hiding place in the garbage can and was one of the 4,000 unfortunates who now stood at the gate and had finished with life. Now a "doctor" - also an SS dog - visited us and took some half-dead people out of the ranks and sent them back to the camp.

Now we were surrounded by sentries and the march began. No sooner had we, the first 500 out of the gate, reached the Bismarck Tower, than the killing began. A Polish prisoner, a Jew from Lodz, collapsed from hunger, and shortly afterwards I heard a shot; the poor man had suffered his end. That was what was in store for all of us now.

The path led to the train station. Incessantly, low-flying American planes roar over our heads. We look up to the sky and everyone's eyes light up, but only for a moment, for then we are called back to bleak reality by the beating and blows of the guards. Above us the liberators, and death strides beside us.

We arrived at Weimar station at 8 o'clock in the evening. An open freight train, packed with prisoners, was just leaving the station. We sat down on the floor. Around midnight we were rounded up, and a train with closed wagons rolled up. Now we had to board at a run, 100 men to a wagon at a time. The hatches were covered with sheet metal and so we could not expect any fresh air. When the last one was inside, the door was pushed shut and locked. We sat in a gloomy hole, emaciated and starved figures, one pressed against the other. Sitting is an exaggeration, for there was no room to stand. A few minutes pass. The train starts. Low whispers. It was up for debate: how long can a malnourished body endure such rigors? Already 24 hours without any food, not a drop of water, not even a chance to defecate. How was this supposed to end?

Suddenly something gets my attention, a Pole pulls out a file from his sleeve, a Russian carefully extracts a crowbar from his trouser leg, another had even thought to bring a small saw. We look at each other and understand each other without saying a word. It's either go on and die, or escape and save our skins, and so all 100 of us men are determined to take the plunge at nightfall. It is about 8 o'clock in the morning,11th April.

Now something happened that was to decide our fate. We hear the sound of an aeroplane, it comes more and more strongly to our ears, on-board weapons whip over our wagons, and ... the inconceivable has occurred, the train stands still. The locomotive is completely destroyed. Bravo, comrades of the R.A.F., you have done a great job. In a few minutes the door is broken open, and we rush out into the open, happy to see daylight once more. Inconspicuously full of jubilation we stretch out our hands towards the sky, towards the Allied airmen. There are yet more victims, for some try to take this chance to escape and are shot in the back.

From far away there is a dull roar, we hear the guns of our liberators. After a few hours of waiting, after more SS troops had arrived to reinforce our guards, we had to line up and march off in the direction of Gera and then on to Dachau. At 7 o'clock that same evening we passed Jena, rushed by the SS. Shortly after, the Jena bridge was blown up. So the Allies had already come pretty close to us. Now the guards are getting anxious. We were driven faster and faster, sweat ran in streams, and even our cry for water was not heard by these brutes.

Feet swelling, I took off my coat and threw it into the ditch to make it easier for me to walk, my companions did the same. Incessant shooting. The SS were at their work again, for whoever could not walk, or stopped once to draw breath, got a bullet, and many, many were exhausted, and stopped dead in the street. All the people who live on the main road No. 7, which leads from Weimar to Gera, are witnesses to these atrocities, for they later had to bury the many murdered themselves.

Now it is getting dark again, but still the pace remains the same. I already feel very weak, because it is already the second day where neither water nor bread have touched my lips. More and more collapse, and just as often the shots crack. All night it went on like this. At four o'clock in the morning, there is an hour's rest. For the first time, after two days and a night. I sway on the grass and am immediately fast asleep. In the afternoon we arrive in Eisenberg.

There we were led to a large pasture and were to get "rations" again after a long time. Completely exhausted, we sat down, and a car came with provisions. But quickly came the great disappointment. In the driver's seat sat the camp commander, SS-Standartenführer (SS Colonel) PRIESTER, and the camp leader, SS-Sturmbannführer (SS Major) SCHOBERT, who told the transport leader, an Obersturmführer (SS Lieutenant), that the rations would be distributed at a factory 7 kilometres away. Thereupon, they got in and drove off. We were now ordered to march off immediately, and the endless train of suffering began to move again. After we had already covered more than 10 km, it became clear to us that we could no longer expect a bite.

It's about 12 midnight. The town of Crossen, which we had just marched through, lies dead and deserted. Incessantly vehicles of the "proud Wehrmacht" roar past us, in hopeless flight. Suddenly there was a terrible bang, flares went up, we stood in the glare and heard the rattle of tanks. An American tank must have apparently advanced directly behind us. It is pitch dark again. Suddenly my fellow sufferer next to me shouts, "I don't see any more guards. We are free." And waking or dreaming, there really was no one left to see from the SS bandits. Finally, after many years, I was free again. But not everything was over yet. I joined a group of 6 boys, and we ran as fast as we could across the field towards the liberators. Suddenly, German soldiers appeared in front of us. What did we do now? Shaven-headed and in prisoner's clothing, they'll recognize us in a minute. Just lie flat on the ground and wait.

Those were anxious minutes. Finally, the air was clear again, and on all fours, we went over the highway. Now take a deep breath. The houses displayed white flags, but no one knew what that meant. On the next main street, there was something quite new for us. In the gutters and sidewalks lay cookies, canned goods, cigarettes, and small packs of "Chewing Gum". Made in USA. We had made it and survived all "hardship". We are under the protection of the Allies, we are FREE.

After a few minutes, we see the first vehicle and the first soldiers. Quickly, we take our prisoner jackets off. Put them on the road and wave. The vehicle stops and when they recognise our uniform, there is an extremely warm greeting. We had tears in our eyes. Our years of wishes, dreams and hopes had come true. Our nerves were completely gone. In the evening we were given princely quarters by an officer, a freshly made real bed and, after an eternity, we slept as human beings again.

I will never forget this 14th of April 1945, the day of my liberation.

Written in happy hours:

Hermann Naidorf,

born 3.6.25 in Gelsenkirchen-Horst

1945: Return to Gelsenkirchen-Horst

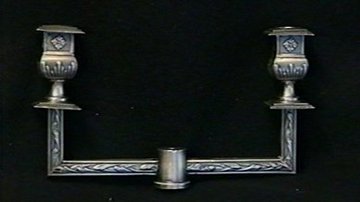

Anna Schmiel, a former employee of the Neudorf family, was able to collect a few items from the family's property on Markenstrasse after the night of the pogrom, and thus save them: a few smashed picture frames with photos of Simon and Frieda Neudorf, the arm of a silver candelabrum, a silver Seder plate and Herman's baptismal gown. "When I returned to Gelsenkirchen, Anna Schmiel gave me these things; she always stood by us. These things, besides my memories, are the only things I have left of my parents. My christening robe, on which my mother once embroidered my name, has also been worn by my three sons and my grandchildren" Herman Neudorf told us.

After his liberation from Buchenwald concentration camp, Herman Neudorf returned to Gelsenkirchen-Horst in 1945 as the sole survivor of his family. He found Mrs. Salfeld, the former neighbour from Markenstrasse 19, in the Hyppolitus School, where she had emergency quarters. Unprompted, she was immediately willing to return to Herman the items stolen from his parents' apartment, mainly articles of clothing. Herman Neudorf then gave away the clothes of his parents, who had been murdered by the Nazis, to needy people in Horst. "Of course, she claimed to have known "nothing of all this," stressing how hard it had been for her during the Nazi era. Her son had also been killed. She must have had a particularly hard time, as a Nazi women's leader and fanatical supporter of the Nazis," was Herman Neudorf's ironic comment in a conversation with Gelsenzentrum.

"Many years have passed since my liberation from the hell of the camps. However, I still cannot believe how such a seemingly cultured people could fall into the hands of a fanatic and from which sprang countless murderers. "Kristallnacht" was the result of a racial hatred that turned once peaceful neighbours into wild animals. May we all hope and be vigilant that such atrocities never happen again...Forgiveness is necessary, but forgetting is impossible!" says Herman Neudorf, now 86 and living in the USA.

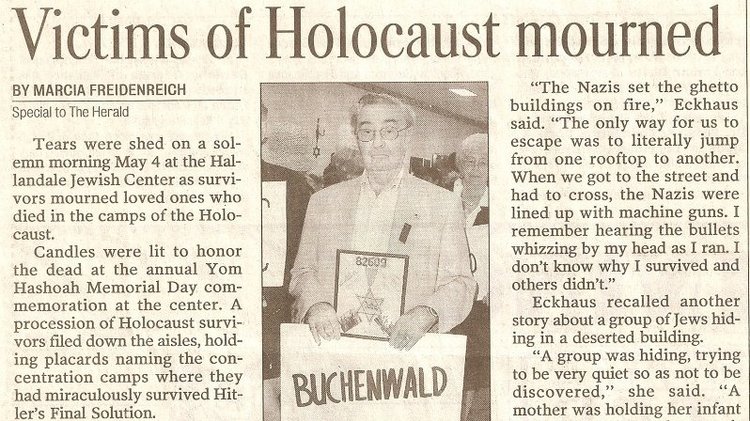

Yom Hashoa 2003 in Halendale Beach, Florida - Victims of Holocaust mourned

February 2008: Train of Remembrance

Since Sunday morning, the "Train of Remembrance" has been standing at the main station in Gelsenkirchen. Herman Neudorf, who was deported in 1938, sent some words for the opening of the exhibition. Neudorf lives in the USA today. In the letter, which was read out at the main station, it says:

"On 28th October 1938, a policeman came to my school, the Realgymnasium Horst - and took me to the prison in Horst. I was just 13 years old. From that day on, my youth was over! From there I was dragged to Poland and then to Riga, to Stutthof concentration camp and to Buchenwald, where I was liberated in 1945. One must forgive - but forgetting is impossible. That's why I wish the 'Train of Remembrance' great success and thank everyone who keeps our fate alive."

On behalf of the initiators, Rüdiger Minow, spokesman for the board of the "Train of Remembrance" association, responded at Gelsenkirchen Central Station:

"Dear Herman Neudorf in the United States,

... It hurts that the murderers ran free in the post-war period and in Gelsenkirchen, as elsewhere, evaded atonement. For decades these perpetrators managed to prevent the deportees from being remembered properly. They denied their deeds and denied their responsibility. Their silence, in Gelsenkirchen as elsewhere, mocked the victims once again. The silence marginalized the survivors who would have been entitled to attention. The same silence deprived us, the sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons of the perpetrators, of the opportunity to mourn. The entire post-war history in Gelsenkirchen, as elsewhere, is permeated by the perpetrators' continued presence. We must express this fact, so that new lies do not make the rounds, lies and justifications, according to which everything had been done early, permanently, and thoroughly to face the Nazi crimes. From such justifications, it is only a small step to political weariness: "Enough, we have done enough." The opposite is true: we have not done enough, we have not cared for the victims early or permanently, and certainly not thoroughly. This is shown by the tremendous popularity of the "Train of Remembrance" because grief, pain, and the shame of tens of thousands find their place there after so many years.

The "Train of Remembrance" travels through Germany, although it is financially hindered. It also comes to places where it was not invited. The "Train of Remembrance" is in Gelsenkirchen because of the more than 90 children and young people who come from your city and who were sent to their deaths.... Dear Herman Neudorf, the harm that was done to you in Gelsenkirchen and Germany when you were 13 years old, the suffering that led to Riga, to Stutthof concentration camp and then to Buchenwald is unforgotten..."

The life story of Holocaust survivor Herman Neudorf

External content

This content from the external provider

YouTube Video

is deactivated for data protection reasons and will only be displayed after your consent.

Agree now to connect with YouTube. For revocation instructions, see Privacy Policy.

External content

This content from the external provider

YouTube Video

is deactivated for data protection reasons and will only be displayed after your consent.

Agree now to connect with YouTube. For revocation instructions, see Privacy Policy.

From the private collection of Herman D. Neudorf. Recorded in 1995 by the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation.

Published on the website of GELSENZENTRUM with kind permission of Herman Neudorf.

The spelling of the first and last name was changed to Herman Neudorf when he immigrated to the United States.

Andreas Jordan, August 2007; supplements December 2011.

Translated by Toby Harrison, November 2021.

With the friendly support of

Gelsenzentrum - Portal for Urban and Contemporary History